Clive Phillpot es un comisario de exposiciones, escritor y bibliotecario inglés. Entre 1977 y 1994 fue Director de la Biblioteca del Museo de Arte Moderno (MoMA) en Nueva York, donde fundó y comisarió la Collección de Libros de Artista. Anteriormente fue el bibliotecario de la Chelsea School of Art, en Londres. Ha escrito y editado numerosos artículos y libros relacionados con el libro de artista, cuyo concepto Phillpot ha contribuido decisivamente a definir. En los años sesenta y setenta el libro de artista emergió como un medio artístico accesible, al ser barato, portátil y distribuido masivamente. En esta entrevista intento comprender si aquellas expectativas han sobrevivido, actualizadas y transformadas en el fenómeno contemporáneo de la novela de artista.

Clive Phillpot

ENTREVISTA A CLIVE PHILLPOT

David Maroto

Realizada entre el 30 de abril y 28 de mayo 2016

[David Maroto:] Entiendo que una de tus misiones cuando tomaste la posición de director de la Biblioteca del MoMA en Nueva York en 1977 fue crear una colección de libros de artista. ¿Cuál era tu objetivo último al crear tal colección? ¿Era la legitimación de un medio artístico incipiente una de tus motivaciones?

[Clive Phillpot:] Debo decir que no fui a MoMA con una misión. Más que como misionario fui como explorador. Sucedió que, a comienzos de 1977, cuando hice la entrevista, se había inaugurado la exposición Bookworks (1977), lo cual coincidía convenientemente con mis intereses. Esto me dio la oportunidad de hablar de mi experiencia con libros de artista. Como resultado de todo esto intuí una puerta abierta a la creación de una colección. Debo añadir que, en aquel tiempo, yo consideraba que una biblioteca que desease documentar arte contemporáneo no podía ignorar el libro de artista como un elemento constituyente de su colección. Por tanto, la cuestión no era «legitimación». Se trataba simplemente de buena praxis.

¿Cómo se integra la colección de libros de artista en MoMA? ¿Es parte de la biblioteca, o es parte de la colección del museo junto con pinturas y esculturas? Me pregunto cómo un visitante podía acceder a la colección de libros de artista. ¿Habilitaste algún tipo de sala teniendo en cuenta las condiciones específicas de lectura que este tipo de obra requiere?

Cuando empecé a descubrir libros de artista en la biblioteca de la escuela de arte en la que trabajé antes de MoMA, pensé que tendría sentido integrarlos en la colección general de la biblioteca, como monografías de artista si fuera necesario, facilitando así el encuentro casual con este tipo de material.

Cuando llegué a MoMA, con su biblioteca de acceso restringido, pensé que colocar este tipo de libros ayudaría a facilitar comparaciones dentro de este campo en expansión, así como a agruparlos para su cuidado y conservación, dado que muchos de ellos se publicaban en pequeñas ediciones. Pero también propuse la supresión de las entradas en el catálogo que los designaban como «libros de artista», de manera que pudieran ser considerados tan relevantes como las monografías de artistas en relación a su utilidad investigadora. De manera que, al camuflar su identidad como libros de artista, se pudieran experimentar sin expectativas previas. Existe una muy buena explicación de la historia del libro de artista en MoMA en el libro de Barbara Bader, Modernism and The Order of Things: A Museography of Books by Artists (Bader, 2010).

La situación actual es que la biblioteca colecciona los libros, relativamente baratos, que yo denominaría «libros de artista», mientras que el Departamento de Dibujos y Grabados colecciona aquellos libros más caros que a menudo utilizan medios de impresión autográfica, y que a veces se refieren como «livres deluxe» [libros de lujo].

Te preguntaba sobre tu experiencia en la creación y gestión de la colección de libros de artista porque resuena con la colección de novelas de artista que estoy creando para otro museo, M HKA, en Amberes. En este caso, tomé como «misión» (probablemente una palabra demasiado grandilocuente) ayudar a generar la percepción de la novela de artista como un medio legítimo dentro de las artes visuales.

Mi propagandismo del libro de artista fue más bien un esfuerzo solitario. Aunque dentro de una institución como MoMA tomé las necesidades y la historia del museo en consideración, me convertí en un «misionero» a través de mis escritos y en mi propio tiempo. Así que ¿nuestras situaciones son quizá diferentes?

En uno de los textos incluidos en Booktrek (Phillpot, 2013:160), cuando hablas del devenir del libro de artista desde una perspectiva actual, mantienes que:

Los sueños de muchos por un arte accesible fueron brutalmente destruidos. Pero algunos elementos de este sueño nunca habían sido muy realistas. Muchos soñaron que los libros de artista pudieran ser vendidos a bajo coste en las cajas de los supermercados, por ejemplo, pero no tuvieron en cuenta el contenido esotérico de la mayoría de los libros de artista existentes.

¿En qué momento te diste cuenta de que las aspiraciones de que el libro de artista fuera una «forma de arte democrática» eran un sueño, más que una realidad efectiva?

Este texto fue uno de mis intentos de explotar la burbuja acrítica que se repetía continuamente en revistas y catálogos de exposiciones. Sin embargo, yo aún pensaba que los libros de artista podían ser, y a menudo lo eran, una forma de arte accesible, incluso desechable. En años recientes, una nueva generación ha estado separando el grano de la paja dentro de las publicaciones de artistas, reeditando algunas obras antiguas que habían aparecido en pequeñas ediciones. Esta es la clave de la accesibilidad: ¡la reedición!

Yo diría que hay dos maneras de entender la accesibilidad (aumentada). Una implica que el libro de artista es barato, portátil y distribuido masivamente. La otra afecta a los contenidos, los cuales deberían ser comprensibles para un público no relacionado con el arte. ¿Sería la confusión entre estas dos la razón por la cual la «fantasía del supermercado» nunca se realizó?

Bueno, David, yo he criticado el hecho de que muchas veces los libros de artista tengan un «contenido esotérico», pero esa objeción estaba de alguna manera exagerada con el fin de atacar los diversos clichés que había en el ambiente. Sin embargo, no es apropiado trazar con una brocha tan gorda dentro de una conversación más calmada y equilibrada, como ésta. Pues en realidad, al menos para mí, es a menudo el contenido esotérico lo que me atrae hacia un libro en primer lugar. De modo que quizá aquí me retraería de la idea de que los libros de artista «deberían ser comprensibles para un público no relacionado con el arte», y decir simplemente que los artistas reflexionan sobre la audiencia potencial de sus publicaciones cuando presentan sus ideas.

Si los libros de artista no fueran relativamente «baratos», «portátiles» e, idealmente, capaces de ser «distribuidos masivamente», yo perdería interés en este medio. El precio, la asequibilidad, nos dice mucho de las aspiraciones del artista/autor.

Me interesa comprender la fantasía de la novela, el escenario imaginario que motiva el deseo del artista por escribir novelas en primer lugar. Tal fantasía, creo, trata sobre todo de una accesibilidad aumentada. Por tanto, me gustaría discutir el libro de artista desde la misma perspectiva, en lugar de nuestro punto de vista desde dentro del mundo del arte. Para nosotros, confrontar contenidos esotéricos puede ser estimulante. Pero, cuando uno quiere distribuir sus libros de artista en una estación de tren, podría ser necesario pensar de manera diferente si se desea alcanzar un público distinto.

Para los artistas, o sus ayudantes, otra manera de conectar libros de artista con trenes, y con el público, ha sido simplemente dejar los libros al azar en los asientos de los trenes para que los viajeros se los lleven si se sienten suficientemente intrigados. Pero, si la estación de tren es tu punto de distribución, entonces conectar con el público no es tan sencillo. De hecho, esta específica plataforma de lanzamiento no tiene para mí ninguna ventaja sobre una tienda de libros, excepto por el hecho de que el libro de artista se acerca mucho más a su público potencial en los abarrotados alrededores de una estación, y que los viajeros suelen tener tiempo disponible.

Conectar un libro de artista con un lector depende de varios factores. Quizá pueda simplificar la situación enumerando tres solamente: el contenido del libro, la apariencia del libro y el coste del libro. ¿Quizá el contenido del libro es menos importante cuando la apariencia y el coste son ambos atractivos? Una presentación visual excelente de un contenido difícil podría ser muy relevante a la hora de distribuir tales ideas.

¿Piensas que la novela de artista, en tanto que declara ser una obra leíble de ficción narrativa, podría cumplir potencialmente con el segundo tipo de accesibilidad? Después de todo, todos estamos entrenados en entender narraciones (a través de la empatía narrativa, por ejemplo) y, en principio, no es necesario contar con un conocimiento especializado para comprender los contenidos de una novela.

De hecho, me parece que la novela de artista, tal como entiendo este tipo de publicación artística, existe en una situación exactamente paralela al libro de artista en general. No parece haber ninguna razón por la cual no debiera ser barata y portátil, y manifestar un contenido bien esotérico o bien fácilmente comprensible.

La mayoría de las novelas de artista que conozco han sido publicadas en forma de libro, en ediciones de bolsillo, en lugar de utilizar tecnologías de publicación digital. Una versión digital (página web, eBook, Kindle, etc.) parece cumplir con las aspiraciones de la obra de arte de ser barata, portátil y distribuida masivamente de manera mucho más efectiva que un libro físico. ¿Por qué crees que los artistas tienen tanto apego al formato libro precisamente en el momento en que su obsolescencia parece irremediable?

Creo que la idea de que «los artistas tienen tanto apego al formato libro» es debatible. El creciente empleo de la expresión «publicaciones de artista» para abarcar libros de artista, revistas de artista, incluso novelas de artista y otras formas, también aquellas que son digitales, parece sugerir que la especificidad de los libros de artista dentro de esta categoría más amplia podría estar en declive. Es posible, sin embargo, que se pudieran metamorfosear en entidades más complejas.

¿Ves un elemento de fetichismo en la producción de libros de artista que pudiera convertirlos en una opción preferida sobre las ediciones digitales? Después de todo, los libros pueden poseerse y coleccionarse, y retienen un componente sensual que su equivalente electrónico no tiene.

El fetichismo de aspectos del libro tradicional era aquello contra lo que se luchaba en los años setenta y ochenta. Esto sucedía en paralelo al incremento de arte de bolsillo barato en aquel momento y, probablemente, como reacción a ello. Hubo un aumento de la exposición de libros hechos por artistas que mostraban materiales o encuadernaciones altamente ostentosos (y flojo contenido), que se volvían algo aún más precioso cuando la edición se componía de una sola copia. Unos libros tan caros y pretenciosos se tornaron en libro-objetos mudos. Pero podrías tener razón al sugerir que hay un elemento de fetichismo en el acto mismo de producir libros de artista hoy o, si no fetichismo, al menos nostalgia, dado el ascenso irresistible de lo digital.

Pero también, frente a tu aserción de que la «obsolescencia del libro parece irremediable», me da la sensación de que debo enfatizar de nuevo qué artefacto tan eficiente es el libro códice y, más allá del mismo, el libro de bolsillo contemporáneo. El códice ha existido durante siglos y la mayoría de tales libros, de tales artefactos, son muy eficientes. (¿Debo recordar que no necesitan pilas?) Sus características comunes son también excepcionales para la facilitación y articulación de narraciones, ya sean verbales, visuales o verbi-visuales. De modo que considero que al viejo perro le queda aún mucha vida. ¡También mencionas que puede poseer una cierta sensualidad! ¡Sí, totalmente!

¿Habría una correlación entre la creación de la colección de MoMA (y la legitimación del medio que acarreó) y el tratamiento como mercancía del libro de artista, tal como ocurre con cualquier otro tipo de obra de arte?

¿Sin duda los libros de artista han sido siempre mercancía? ¿La mayoría de libros de artista existen, aunque sea de manera precaria, en el mundo de la edición y la distribución?

Me refería a mercancía en el sentido de que un libro de artista que originalmente costara, por ejemplo, dos dólares, ahora cueste dos mil dólares porque su estatus en el mundo del arte ha cambiado. Me preguntaba qué factores influyeron en la causa de tal cambio y, por consiguiente, de tal aumento de precio.

Ya había entendido a lo que te referías, pero primero quería enfatizar que estas publicaciones han de existir en la misma economía que otras publicaciones han de negociar. Pero creo que podemos hablar de dos criterios que afectan al tratamiento como mercancía al que te refieres. El primero es el tamaño de la edición, el segundo es el valor intelectual o estético. ¡Ediciones pequeñas equivalen a libros raros! Pero un libro puede ser raro y aun así no tener valor económico si el valor estético es nulo. Es cuando este segundo atributo es relevante y se combina con la raridad que el precio de mercado se dispara estratosféricamente. Y, por supuesto, que un valor estético se mantenga en el tiempo es casi impredecible, ya que es el producto de muchas sensibilidades diferentes.

En tu texto Books by Artists and Books as Art (Phillpot, 1998:38), enumeras una serie de categorías derivadas del libro de artista:

Entre las muchas categorías en este espectro se encuentran las siguientes: números de revistas y obras en revistas; ensamblajes y antologías; textos, diarios, declaraciones y manifiestos; poesía visual y obras con palabras; partituras; documentación; reproducciones y libros de apuntes; álbumes e inventarios; obra gráfica; cómics; libros ilustrados; arte en páginas, obras en páginas y arte postal; y arte con libros y obras en libros.

Me llamó la atención que no mencionaras la novela de artista. Me pregunto por qué ha sido ignorada por el mundo del arte durante tanto tiempo.

Tienes razón David, no incluí novelas de artista en mi espectro de libros de artista. Ante todo he de decir que mis categorías no pretendían ser completas o exclusivas, y que los libros de artista son mestizos. Simplemente intenté indicar la abundancia de material que podría ser abarcado por el término «libro de artista». (Una motivación secundaria fue el intento de incorporar «libros ilustrados» en este terreno.)

En cuanto a «novela de artista», no pensé en tal categoría, y del mismo modo tampoco pensé en poesía de artista ni en novela de contable. Para mí la novela es una forma literaria específica que puede ser empleada por cualquier grupo que la practique. Además, la mayoría de las veces, hasta las novelas «experimentales», por ejemplo, son literarias, mientras que, en contraste, los libros de artista pueden cuestionar cualquier aspecto del libro y, en cualquier caso, son con frecuencia entidades visuales o verbi-visuales.

Ahora bien, tú está mucho más enterado de la gama de material que constituye las «novelas de artista», así que espero que me cuentes de qué manera tendría sentido la inclusión de novelas de artista en mi «espectro».

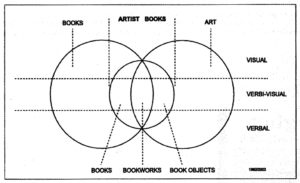

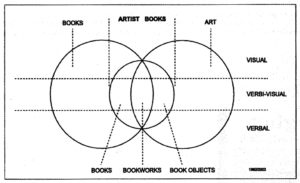

Figura 1: Clive Phillpot: Diagrama (2003). En: Nordgren, S. y Phillpot, C. (Eds.) Outside of a Dog. Gateshead: Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, p. 4.

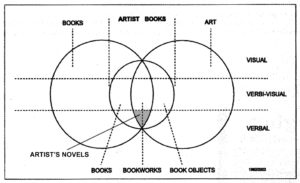

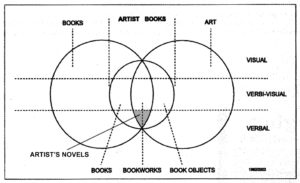

Figura 2: Diagrama alterado para mostrar la inserción de la novela de artista.

Estoy de acuerdo en que la novela es un género literario que puede ser practicado por cualquiera. Por tanto, en principio, una novela escrita por un artista visual no tendría por qué ser un objeto diferente a una novela escrita por un contable, un marinero o un escritor profesional. De hecho, este tipo constituye la mayor porción de las novelas escritas por artistas visuales que he encontrado.

Sin embargo, dentro de esos 440 títulos,[1] existe un grupo más reducido que llamo específicamente «novelas de artista», las cuales son empleadas por los artistas en sus proyectos exactamente de la misma manera que emplean vídeo o instalación, por ejemplo. Uno es libre de leer una novela de artista solamente como una pieza literaria, pero entonces uno se perdería la mayoría de los contenidos de la obra. Los cuales no residen sólo en el texto impreso en sus páginas, sino también, y principalmente, en el proceso de creación. Desde esta perspectiva, una novela de artista es una obra de arte que se apropia de la estructura y convenciones de una novela.

Por ejemplo, una novela de artista tal como Headless (Goldin+Senneby, 2015) declara ser una novela de misterio. Pero, en realidad, es una de las obras creadas en un proyecto artístico a lo largo de siete años. Headless aborda cuestiones artísticas por medio de recursos literarios tales como la narración y la ficción. Fue producida dentro del mundo del arte y debería ser leída dentro de ese contexto si uno quiere apreciar las auténticas implicaciones de la obra.

Algo que encuentro sorprendente es la falta de literatura sobre novelas escritas por artistas, por no hablar de novelas de artista. Éste no es el caso de la poesía. Poesía surrealista, poesía visual, poesía concreta y, más recientemente, Uncreative writing [Escritura no creativa], todas ellas son híbridos bien conocidos entre la poesía y las artes visuales. Me gustaría conocer tu opinión sobre la diferencia en el interés generado históricamente en el mundo del arte por estos dos géneros literarios.

Figura 3: Goldin+Senneby: Headless: Each Thing Seen Is the Parody of Another or Is the Same Thing in a Deceptive Form (instalación de sonido, 2010). Moderna Museet, Estocolmo. Fotografía: Albin Dahlström.

Me parece que ya he sugerido que mi propio conocimiento de la novela de artista ha sido escaso. Y quizá hay muchos otros que tampoco han sido conscientes de la existencia o sustancia de esta categoría. De modo que, si existe ese vacío en la literatura sobre este tema, ¿me da la sensación de que alguien como tú, con tu conocimiento y entusiasmo, está idealmente equipado para llenar ese hueco?

Por otro lado, ¿quizá la novela de artista no sea un compañero de cama natural entre otros medios artísticos? Me ayudaría si pudiera leer lo que tienes que decir sobre los rasgos distintivos de la novela de artista que realmente la posicionan dentro del arsenal del artista visual, en lugar de entre el conglomerado de autores novelísticos en general. ¿Cómo hace el artista para trocar la forma novelística en una declaración artística visual?

Debo decir que mi investigación no se ocupa tanto de aquello que la novela de artista es como de aquello que la novela de artista hace dentro de las artes visuales. Todos sabemos lo que es un urinario. Es exactamente el mismo objeto cuando está en un baño público y cuando está en un pedestal. Pero lo que hace en un pedestal en una exposición de arte es muy diferente. Tanto que se convierte en un nuevo medio en las artes visuales y pasa a llamarse ready-made. Mi aproximación a la novela de artista es similar.

Quizá algunos de los experimentos llevados a cabo por artistas en sus novelas hayan sido realizados por escritores anteriormente. Sin embargo, no trato la novela desde un punto de vista literario, sino artístico. Por tanto, nociones que pudieran ser convencionales (cuando no conservadoras) en el mundo literario abren un vasto campo de acción en la práctica artística. La novela de artista funciona como vehículo para introducir nociones tales como narración, ficción, identificación e imaginación en la obra del artista, tanto en la novela de artista como en la obra asociada a la misma (por ejemplo, en un ciclo de performances narrativas y episódicas que estimulan la imaginación de la audiencia por medio de una narración oral).

De forma similar, para un escritor es evidente que leer una novela lleva tiempo. Desde un punto de vista artístico, esto puede convertirse en una herramienta para decelerar la experiencia artística. Pasar días o semanas en contacto con la obra requiere un compromiso extendido, el cual contradice el tiempo que solemos pasar frente a una obra de arte.

Todo se reduce a una cuestión de legibilidad. El artista aspira a producir una obra que sea capaz de cautivar a través del placer de la lectura. Sin embargo, no estoy afirmando que ésta sea la realidad de la obra, sino parte de la fantasía que el artista tiene sobre la novela. No obstante, es la fantasía la que motiva al artista a explorar medios innovadores para cumplirla. ¿Crees que esta explicación de la fantasía de la novela podría resonar, al menos parcialmente, con una anterior «fantasía del libro de artista»?

Sí, así lo creo. Una palabra que saltó a mi vista en tu párrafo anterior es «placer». Ciertamente el placer, aunque raramente se habla de él, es un elemento esencial al leer tanto libros de artista como novelas de artista (entendiendo «leer» en el más amplio sentido). Tu enumeración de las funciones de la novela de artista sugiere que pueden ser apreciadas de manera muy similar a otras publicaciones.

La novela de artista conlleva dos grandes desafíos: ¿cómo leerla, cómo exponerla? ¿Se supone que uno ha de leer una novela de artista entera en el museo? ¿Debería leerse en conexión con el contexto artístico del que procede? Anteriormente, mi pregunta sobre la forma en que facilitaste la lectura de libros de artista en la colección de MoMA (y si eso se había hecho por medio de una sala de lectura específica) apuntaba en esta dirección.

Bien, libros de artista y novelas de artista pueden (debieran) ser leídos en un entorno cómodo, tal como un entorno doméstico. Pero los usuarios de una biblioteca están también acostumbrados a leer durante largos periodos en una institución, de manera que lugares como las bibliotecas pueden ser apropiados para sesiones de lectura. Más allá existe el banco en el parque, el césped, etc. Se podría decir que el entorno del museo es el menos apropiado para leer.

Exponer libros, que normalmente existen como artilugios portátiles móviles, como objetos abiertos por una página bajo un cristal, es claramente problemático. ¿Quizá, idealmente, uno debería adquirir al menos dos copias de cada publicación representada en una colección? Esto aseguraría que una copia permaneciera cerrada (o abierta por un único lugar) por largos periodos de tiempo, mientras que a la otra copia se le puede permitir deteriorarse a través del uso frecuente.

A los usuarios de la biblioteca de MoMA se les daba la oportunidad de manipular la mayoría de las publicaciones de la colección, incluyendo libros de artista, dentro de los confines de la sala de lectura. Por supuesto, se colocaban dispositivos de seguridad para proteger las obras frágiles, pero esta disposición todavía no se podría comparar con la facilidad de consulta en tu propia casa.

Si no es posible presentar obras frágiles para que sean manipuladas de manera segura en el entorno museístico, existe alguna alternativa a la que recurrir. En particular, se podría hacer un vídeo para grabar una sola toma de contacto inicial con el libro que en adelante se pueda reproducir multitud de veces sin riesgo para el volumen original. Otros tipos de facsímiles se podrían presentar igualmente.

Bibliografía

Bader, B. (2010). Modernism and the order of things: A museography of books by artists. Saarbrücken: Suedwestdeutscher Verlag fuer Hochschulschriften.

Bookworks (1977) [exposición]. Museo de Arte Moderno, Nueva York. 17 Marzo–31 Mayo.

Goldin+Senneby [K.D., pseud.] (2015). Headless. Berlín/Nueva York/Stockholm: Sternberg Press/Triple Canopy/Tensta Konsthall.

Phillpot, C. (1998). «Books by artists and books as art». En Phillpot, C. y Lauf, C. (Eds.), Artist/author contemporary artists’ books (pp. 30–55). Nueva York: Distributed Art Publishers.

Phillpot, C. (2003) «Bookworks, mongrels, etcetera». En: Nordgren, S. y Phillpot, C. (Eds.), Outside of a dog (pp. 2–4). Gateshead: Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art.

Phillpot, C. (2013). Booktrek. Zurich/Dijon: JRP | Ringier/Les presses du réel.

[1] Esta cifra corresponde al dato del 10 de mayo de 2016.

Clive Phillpot is an English curator, writer, and librarian. Between 1977 and 1994 he was the Director of the Library at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where he founded and curated the Artist Books Collection. Previously, he was the librarian at the Chelsea School of Art in London. He has written and edited numerous articles and books on the topic of the artist’s book,[1] whose concept he decisively contributed to define. In the 1960s and 1970s the artist’s book emerged as an accessible art medium by being cheap, portable, and mass distributed. In this interview I tried to learn whether those expectations have survived, updated and transformed in the contemporary phenomenon of the artist’s novel.

Clive Phillpot

INTERVIEW WITH CLIVE PHILLPOT

David Maroto

Held between 30 April–28 May 2016

[David Maroto:] I understand that one of your missions when you took the position as head of the library of the MoMA in New York in 1977 was to create a collection of artist’s books. What was your ultimate goal by creating such collection? Was the legitimation of an incipient artistic medium one of your motivations?

[Clive Phillpot:] I should say that I did not go to MoMA with a mission. I went instead as an explorer, not a missionary. It so happened that early in 1977 when I went there for my interview, their exhibition Bookworks (1977) was on display, which coincided nicely with my interests. This also gave me the opportunity to talk about my experience with artist books. The result was that I felt there was an open door to proceed with making a collection. I should also say that by this time I considered that any library wishing to document contemporary art could not ignore artist books as a constituent element of the collection, thus ‘legitimation’ was not an issue. It was just good practice.

How does the artist’s books collection sit in MoMA? Is it part of the library or is it part of the museum’s art collection, along with paintings and sculptures? Also, I was wondering how a visitor would access the artist’s books collection. Did you enable some sort of reading room considering the specific conditions of readership that such works would demand?

When I was beginning to discover artist books at the art school library where I worked, before MoMA, I thought it made sense to integrate them in the broader library collection, where appropriate as artist monographs. Thus facilitating chance encounters.

Having arrived at MoMA, with its closed access library, I then thought that collocating such books would have a value in facilitating comparisons within this expanding field, as well as grouping them for care and conservation, given that they were often published in small editions. But I proposed the suppression of cataloguing records that designated them as ‘artist books’ so that they might be considered as relevant as artist monographs in regard to their utility for research; as well, in a sense, to camouflage their identity as artist books, so that they might therefore be experienced without expectations. There is a very good account of the history of artist books at MoMA in Barbara Bader’s Modernism and The Order of Things: A Museography of Books by Artists (Bader, 2010).

The current situation is that the library collects the relatively inexpensive books that I would nominate as ‘artist books’ while the Drawings and Prints Department collects those more expensive books that often utilize autographic print media, sometimes called ‘livres deluxe’.

I asked about your experience with creating and managing the collection of artist’s books because it resonates with the artist’s novels collection that I am creating for another museum, M HKA in Antwerp. In this case, I took it as a ‘mission’ (probably a too grandiloquent word) to help to generate the perception of the artist’s novel as a legitimate medium in the visual arts.

My propagandising for artist books was more of a solo effort. In an institution like MoMA I took the museum’s needs and history into consideration, and became a ‘missionary’ in my own time and my own writing. So maybe our situations are different?

In one of the texts included in Booktrek (Phillpot, 2013:160), when talking about the fate of the artist’s book from a present perspective, you state that:

The dreams of many for accessible art were rudely shattered. But some ingredients of this dream had never been very realistic. The dream that artists’ books could be sold cheaply at supermarket checkout points, for example, disregarded the arcane content of most existing artists’ books.

At which point did you realise that the aspirations for the artist’s book to be a ‘democratic art form’ were a dream rather than an effective reality?

This piece of writing was one of my attempts to burst the uncritical bubbles that were repeated over and over again in magazines and exhibition catalogues. However, it was still my belief that artist books could be, and often were, accessible – even expendable – art forms. In recent years another generation has been winnowing artist publications and choosing to reprint earlier works that originally appeared in small editions. This is the key to accessibility. Reprinting!

I would say that there are two ways of understanding (increased) accessibility. One implies that the artist’s book is cheap, portable, and mass distributed. The other one affects the contents, which should be comprehensible to non-art related audiences. Would the confusion between these two be the reason why the ‘supermarket fantasy’ was never realised?

Well, David, I have criticised artist books as often having ‘arcane content’ but that objection was rather overdone in order to attack the various clichés that were in the air. However, to paint with such a broad brush in a calmer more balanced discussion such as this one, is not appropriate. For in reality, for me at least, it is often arcane content that draws me in to a book in the first place. So perhaps I would here pull back from the idea that artist books ‘should be comprehensible to non-art related audiences’, and say simply that artists might reflect on the potential audience for their publications when they are packaging their ideas.

If artist books were not relatively ‘cheap’, ‘portable’, and ideally capable of being ‘mass distributed’ I would lose interest in the medium. The price, the affordability, tells us about the aspirations of the artist/author.

I am interested in understanding the fantasy of the novel, which is the imaginary scenario that drives the artists’ desire to write novels in the first place. Such fantasy, I believe, is mainly about increased accessibility. Thus, I wanted to discuss the artist’s book from the same perspective, rather than from our art-world point of view. For us, to confront arcane contents might be exciting. But when one wants to distribute one’s artist’s books in a train station, it might be necessary to think differently if one wishes to reach a different audience.

Another way of connecting artist books with trains, and with a public, has been for the artists, or their helpers, to simply leave books randomly on the seats of trains for commuters to take away should they be sufficiently intrigued. But if the train station is your distribution site then connecting with an audience is not so simple. In fact this specific launch pad seems to me to have no advantage over a bookstore, except for the fact that the artist books get much closer to their potential audience in the cramped surroundings of a station, and that commuters often have time on their hands.

Connecting an artist book with a reader depends upon several factors. Perhaps I can simplify the situation by listing just three: the content of the book, the look of the book, and the cost of the book. Perhaps the content of the book is less of an issue when the look and the cost are both attractive? Excellent visual presentation of difficult content might be very significant in helping such ideas to travel.

Do you think that the artist’s novel, insofar as it claims to be a readable work of narrative fiction, could potentially fulfil the second kind of accessibility? After all, we are all trained in understanding narratives (through narrative empathy, for instance) and, in principle, no one needs a specialised knowledge to comprehend the contents of a novel.

Actually, it seems to me that the artist novel, in so far as I understand this kind of artist publication, exists in an exactly parallel situation to artist books in general, in that there seems to be no reason why it should not be cheap and portable, and manifest content either arcane or easily comprehensible.

Most of the artist’s novels I know have been published as books, in paperback editions, instead of making use of digital publishing technologies. A digital version (website, eBook, Kindle, etc.) seems to fulfil the aspirations of the artwork to be cheap, portable, and mass distributed much more accomplishedly than a physical book. Why do you think that artists are so attached to the book format exactly at the time when its obsolescence appears to be irredeemable?

I think that the idea ‘that artists are so attached to the book format’ is debateable. The increasing use of the phrase ‘artists’ publications’ to embrace artist books, artist magazines, even artist novels and other forms, including those that are digital, seems to me to suggest that the specificity of artist books within this broader category, might now be in decline. It is possible, however, that they could metamorphose into more complex entities.

Do you see an element of fetishism in the production of artist’s books that would make it the preferred option over digital editions? After all, books can be possessed and collected, and retain a sensuous component that its electronic counterpart has not.

Fetishism of aspects of the traditional book was what was being fought against in the 1970s and 1980s. This happened in parallel with the rise of cheap paperback art at that time, and probably as a reaction to it. There was an increase in the exposure of books made by artists that featured highly conspicuous materials or bindings (and feeble content), made even more precious when the edition comprised only one copy. Such overblown and expensive books veered into becoming mute book objects. But you might be right in suggesting that there is an element of fetishism in the very act of producing artist books today or, if not fetishism, then nostalgia, given the apparently irresistible rise of the digital.

But then again, in the face of your assertion that the book’s ‘obsolescence appears to be irredeemable’, I feel that I must re-emphasise what an efficient device is the codex book and, beyond this, the contemporary paperback. The codex has been around for centuries, and most such books, such devices, are very efficient. (Do I need to repeat that they do not require batteries?) Their common features are also remarkable for facilitating and articulating narratives, whether verbal, visual or verbi-visual. So I reckon that there is a lot of life left in the old dog yet. You also mention that they can possess a certain sensuousness! Yes, indeed!

Would there be a correlation between the creation of the MoMA collection (and the legitimation of the medium that it entailed) and artist’s books becoming commodified like any other artwork?

Surely artist books were always a commodity? Most artist books exist, however precariously, in the world of publishing and distribution?

I was meaning commodified in the sense that an artist’s book, which originally cost, for instance, $2, would now cost $2,000 because its status in the art world has changed. I was wondering what factors played a part in causing such change and consequently such increase in value.

I understood what you were getting at, but wanted to stress first that these publications have to exist in the same economy that other publications have to negotiate. But I think that we can talk of two criteria that affect the commodification to which you refer. The first is the size of the edition, the second is the intellectual or aesthetic value. Small editions equal rare books! But a book can be rare and still have no financial value if the intellectual or aesthetic value is nil. It is when this second attribute is both significant and is coupled with rarity that the market price shoots into the stratosphere. And, of course, sustained aesthetic value is almost unpredictable as well as being the product of many sensibilities.

In your text Books by Artists and Books as Art (Phillpot, 1998:38), you enumerate a series of categories derived from the artist’s book:

Among the many categories in this spectrum are these: magazine issues and magazineworks; assemblings and anthologies; writings, diaries, statements, and manifestos; visual poetry and wordworks; scores; documentation; reproductions and sketchbooks; albums and inventories; graphic works; comic books; illustrated books; page art, pageworks, and mail art; and book art and bookworks.

It caught my attention that you did not mention the artist’s novel. I wonder why it has been disregarded by the art world for so long.

You are right David, I did not include artist novels in my artist books spectrum. First of all I should say that my categories were not meant to be exclusive or complete, and that artist books are mongrels. I was just trying to indicate the wealth of material that might be embraced by the term ‘artist book’. (A secondary motivation was an attempt to incorporate ‘illustrated books’ in this terrain.)

As for ‘artist novels’ I did not think about such a category, and in the same way neither did I think about poets’ novels or even accountants’ novels. To me the novel is a specific literary form that can be utilised by any group of practitioners. In addition most of the time even ‘experimental’ novels, for example, are literary, whereas by contrast artist books can question every aspect of the book, and are frequently visual or verbi-visual entities in any case.

Now you are much more aware of the range of material that constitutes ‘artist novels’, so I hope to learn from you in what way the inclusion of artist novels in my ‘spectrum’ would make sense?

Figure 1: Clive Phillpot: Diagram (2003). In: Nordgren, S. and Phillpot, C. (Eds.) Outside of a Dog. Gateshead: Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, p. 4.

Figure 2: Altered diagram showing the insertion of the artist’s novel.

I agree that the novel is a literary genre that can be practiced by anyone. Thus, in principle, a novel written by a visual artist would not have to be a different object than a novel written by an accountant, a sailor or a professional writer. These, in fact, constitute the larger portion of the novels written by visual artists that I have found.

However, within those 440 titles,[2] there is a smaller group that I call specifically ‘artist’s novels’. These are employed by the artists in their projects in exactly the same way that they employ, for instance, video or installation. One is free to read an artist’s novel solely as a work of literature, but then one would miss most of the contents of the work. These lie not only in the text printed on its pages, but also, and primarily, in the process of creation. From this point of view, an artist’s novel is an artwork that appropriates the structure and conventions of a novel.

For example, an artist’s novel such as Headless (Goldin+Senneby, 2015) claims to be a mystery novel. But, actually, it is one of the works created throughout a seven-year-long art project. Headless addresses artistic issues by means of literary devices such as narrative and fiction. It was produced within the art world and it should be read within this context if one is to appreciate the actual implications of the work.

Something that I find surprising is the lack of literature on novels written by artists, let alone the artist’s novel. This is not the case with poetry. Surrealist poetry, Visual poetry, Concrete poetry and, more recently, Uncreative writing, they are all well-known hybrids between poetry and the visual arts. I would like to know your opinion about the difference in the interest historically stirred in the art world by these two literary genres.

Figure 3: Goldin+Senneby: Headless: Each Thing Seen Is the Parody of Another or Is the Same Thing in a Deceptive Form (sound installation, 2010). Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Photo: Albin Dahlström.

I guess that I have already suggested that my own awareness of the artist novel has been slight. And perhaps there are many others who have not been aware of the existence or substance of this category either. So if there is this gap in the secondary literature it seems to me that someone like you, with your knowledge and zeal, is ideally equipped to fill this void?

Alternatively, perhaps the artist novel is not such a natural bedfellow in among other artists’ media? It would help me if I could read what you have to say about the distinguishing features of the artist novel that really position it clearly in the armoury of the visual artist, rather than among the conglomerate authorship of novels in general. How does the artist twist the novel form into a visual art statement?

I must say that my research is concerned not so much with what the artist’s novel is as with what the artist’s novel does to the visual arts. We all know what a urinal is. It is exactly the same object when in a public toilet and when on a pedestal. But what it does on a pedestal in an art exhibition is very different. So much so, that it becomes a new medium in the visual arts and it is then called ready-made. My approach to the artist’s novel is similar.

Perhaps some of the experiments carried out by artists with their novels were done by writers before. However, I am not discussing the novel from a literary point of view, but artistic. Thus, notions that could be conventional (if not conservative) in the literary world can open a vast field of action in art practice. The artist’s novel functions as a vehicle to introduce notions such as narrative, fiction, identification, and imagination in an artist’s work, both in the artist’s novel itself and in the body of work associated to it (for instance, in a cycle of episodic, narrative performances that incites the audience’s imagination by means of storytelling).

Similarly, for a writer it is obvious that reading a novel takes time. From an artistic point of view, it can be a tool to decelerate the artistic experience. Spending days or weeks in contact with the work requires a protracted engagement from the audience, which is at odds with the time we usually spend in front of an artwork.

It all comes to a matter of readability. The artists aspire to produce a work that is able to engage through reading pleasure. But then again, I am not saying this is the reality of the work, but part of the artist’s fantasy of the novel. However, it is fantasy which motivates artists to search for innovative means to accomplish it. Do you think that this account of the fantasy of the novel would resonate, at least partially, with a previous ‘fantasy of the artist’s book’?

Yes, I would think so. A word that jumped out at me from your preceding paragraph was ‘pleasure’. Surely pleasure, though infrequently referred to, is an essential element of reading both artist books and artist novels (‘reading’ being understood in its widest sense). Your listing of the artist novel’s functions suggests that they can be appreciated in very similar ways to other publications.

The artist’s novel poses two major challenges: how to be read? How to be exhibited? Is one expected to read a whole artist’s novel in a museum? Should it be read in connection with the artistic context where it comes from? Earlier, my question about the way you facilitated the reading of artist’s books in the MoMA collection (and whether that was done by means of a dedicated reading room) was pointing in this direction.

Well, artist books and artist novels can – should – be read in a comfortable setting, such as a domestic one. But library users are also well accustomed to long periods of reading in institutions, so places such as libraries can also be appropriate for reading sessions. Beyond this there is the park bench, the long grass, etc. One might say that the museum environment is the least appropriate one for reading.

Exhibiting books that normally exist as mobile hand-held devices, as one-opening-objects under glass, is clearly problematic. Perhaps, ideally, one should acquire at least two copies of every publication represented in a collection? This would ensure that one copy could remain closed (or be open at only one place) for long periods of time, while the other copy can be allowed to deteriorate through frequent use.

The users of the MoMA Library were given the opportunity to handle most publications in the collection, including artist books, within the confines of the reading room. Of course, safeguards were in place to protect fragile works, but this arrangement still does not compare with the ease of consultation in one’s own home.

If it is not possible to safely present fragile works for handling in museum settings, there are one or two alternatives to fall back on. In particular a video might be made to record a single initial engagement with a book which can thereafter be played again and again at no further risk to the original volume. Other kinds of facsimiles might also be presented.

Bibliography

Bader, B. (2010). Modernism and the order of things: A museography of books by artists. Saarbrücken: Suedwestdeutscher Verlag fuer Hochschulschriften.

Bookworks (1977) [exhibition]. Museum of Modern Art, New York. 17 March–31 May.

Goldin+Senneby [K.D., pseud.] (2015). Headless. Berlin/New York/Stockholm: Sternberg Press/Triple Canopy/Tensta Konsthall.

Phillpot, C. (1998). Books by artists and books as art. In Phillpot, C. and Lauf, C. (Eds.) Artist/author contemporary artists’ books. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, pp. 30–55.

Phillpot, C. (2003) Bookworks, mongrels, etcetera. In: Nordgren, S. and Phillpot, C. (Eds.) Outside of a dog. Gateshead: Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, pp. 2–4.

Phillpot, C. (2013). Booktrek. Zurich/Dijon: JRP | Ringier/Les presses du réel.

[1] In this interview, Clive Phillpot uses ‘artist book’ and ‘artist novel’, whereas I use ‘artist’s book’ and ‘artist’s novel’ in order to keep consistency with these terms as they appear throughout my research.

[2] This number corresponds to the data on 10 May 2016.