Paula V. Alvarez: You define SOCKS as a “non-linear journey through distant territories of human imagination”. I am personally very interested in contextualizing this definition in relation with the transformation of our habitat (and design conditions) under the development of media technology along the past two decades. The convergence of territory, imagination, design and media counters the regular perception of mental spaces as something separable of the physical realm. I find surprising that almost hundred years after Surrealists proposed the territories of thinking as a field to be explored in its own right —with no relation to ethics, aesthetics nor reason— we are still stuck in this approach to mental spaces as a separate domain. Very few architects are exploring the substantially different current condition, defined by the assembling of mental realms, conceptual constructions, material and immaterial arrangements, with a great impact in our environment, and also in ethics, aesthetics and thinking. One of the decisive aspects of this new condition, in my view, is how communication and representation often merge to transform reality itself, which implies that those territories between the real, speculation and interpretation, constitute a precious subject of inquiry, and so it seems to be for SOCKS. Considering your visual atlas as an interconnected whole —not just isolated pieces— I always get the feeling that you’re exploring the power of visual thinking to offer an insight into this new realm, penetrating wherever sensory perception or words can’t do. This interpretation is very personal —perhaps biased— but I’d like to know if you somehow engage with it. What are Socks’ premises in approaching our perception and understanding of today’s environments? What role has imagination (and architectural imagination) in it?

We completely identify with your interpretation and we are actually glad that you elaborated this question since it is at the core of our work and interests and you couldn’t express it any better.

When we started to look for a subtitle for Socks, just about a year ago, it was difficult to find a definition that could be comprehensive of the disparate things we use to publish without being too generic, or even worse, ending up with slogans. The idea of “territory” happens to naturally respond to our need, as we imagine to be conducting a perpetual journey during which different fragments of places are slowly revealed on the same surface, even if they belong to distant epochs and areas, to the realm of the constructed world as well as to that of the imagination.

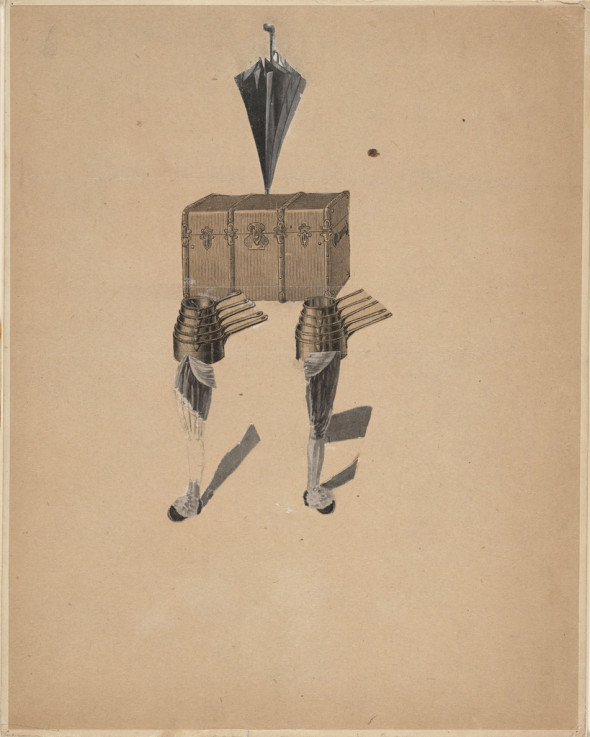

Your reference to Surrealism is very appropriate, because contemporary relation with information and culture seems to us a kind of “exquisite corpse”, a poetic technique introduced as a game by André Breton, (among others), and later adopted by William Burroughs, and even by Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid in their early joint architectural ventures. The difference is that the poetic work happens today as result of the collaborative endeavour of millions of strangers, unintentionally cutting-up and assembling texts, images and videos from all epochs.

Cadavre Exquis with André Breton, Max Morise, Jeannette Ducrocq Tanguy, Pierre Naville, Benjamin Péret, Yves Tanguy, Jacques Prévert (1928). Image via Art History project.

Cadavre Exquis with André Breton, Max Morise, Jeannette Ducrocq Tanguy, Pierre Naville, Benjamin Péret, Yves Tanguy, Jacques Prévert (1928). Image via Art History project.

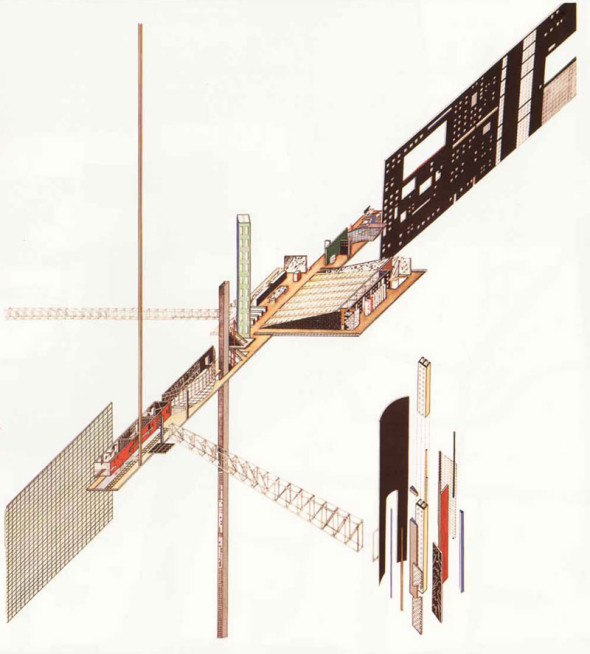

Cadavre exquis: The Competition for the Dutch Parliament Extension, OMA (Koolhaas, Zenghelis, Zaha Hadid) – 1978. Plate : ‘The Ambulatory and its Connections’. Image via: International.

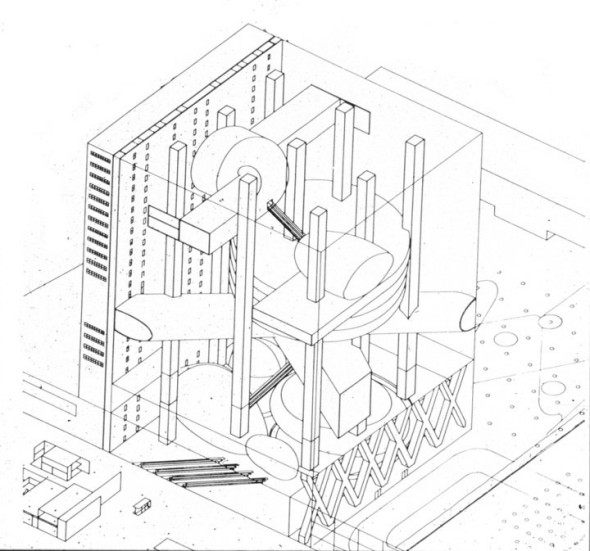

Cadavre exquis: The Competition for the Dutch Parliament Extension, OMA (Koolhaas, Zenghelis, Zaha Hadid) – 1978. Plate : ‘The Ambulatory and its Connections’. Image via: International.

People, all of us included, spend increasing time in environments that, despite lacking “physical” substance, in the end are “real” as well. These spaces (being them architectural designs, social networks, or video-games environments) have been imagined and shaped and they occupy a large slice of our time and our life; they may even be richer or more engaging respect of what we experience in daily environments, so how come we keep considering them something else from reality? We have recently assisted at some events which took place in virtual realms which revealed a meaningful experience and a profound aesthetic value; two examples might be the online mourning of Leonard Nimoy in the “Star Trek” MMORPG and the epic battle of the Titans spaceships in the massive multiplayer online game “Eve Online”, for which thousands of people from all over the world have been continuously engaged for 21 hours. While we rarely write about these phenomena in Socks, we are conscious of their impact and progressive relevance in the shape of our present imaginary.

The epic battle of the Titans spaceships in the massive multiplayer online game “Eve Online”. Image via: Wired.

The epic battle of the Titans spaceships in the massive multiplayer online game “Eve Online”. Image via: Wired.

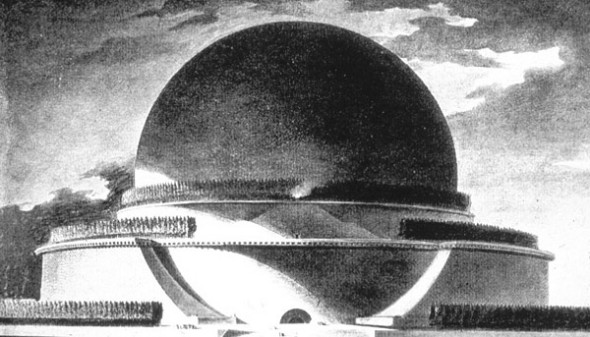

Even before these contemporary examples, the intersection and mutual dialogue between tangible and imagined realms have always been vast, as the significance of many unbuilt projects (Etienne Boullée’s ‘Cenotaph for Sir Isaac Newton’, Cedric Price’s ‘Fun Palace’, or OMA’s ‘Très Grande Bibliothèque’, to name just a few examples) is very well known to architects. But it is just in recent times that the two territories and all the intermediate states between them are increasingly blurring.

Just a short time ago, William Gibson, who might be considered the conceptual inventor of Virtual Reality, after testing the last model of a headset device set to experience VR environments, declared that what he used to imagine in his early novels has finally become real. After more than three decades of tests and failures, technology has now reached a point where the distance between the perception of the physical and the virtual world might get really short, so what we are talking about will probably become of even more actuality in the next few years.

This perspective provides a small glimpse into the future, opening ample possibilities for the building of new design’s tools and the shaping of new environments, but as you mentioned, if we already look at the last two decades the interconnections have become so relevant that denying them seems not only completely pointless, but somehow risky. The risk —not only for architects— is to believe that the only field which might concern our discipline is the physical realm and then find ourselves completely irrelevant respect to realities which deeply shape human life and in which more and more daily time is spent. Of course, as you also mentioned, there are critical questions arising in parallel. The technology that today allows the merging of distant territories, also enable pilots to fly drones from completely safe environments (exactly as in the case of a “safe” flight simulation video game) and kill real people in war zones distant thousands of kilometers.

Online mourning of Leonard Nimoy in the “Star Trek” MMORPG.

Online mourning of Leonard Nimoy in the “Star Trek” MMORPG.

Etienne Boullée’s ‘Cenotaph for Sir Isaac Newton’. Image via: Wikipedia.

Etienne Boullée’s ‘Cenotaph for Sir Isaac Newton’. Image via: Wikipedia.

What we try and do from our perspective is to place artistic researches and utopian studies on a comparable level with built projects, so that it is possible to visualize how what might look as faraway approaches actually touch each other and how we can identify common tools to investigate and intervene on one or another realm. Unexpected methodologies can emerge because critical approaches can be constructed and deconstructed by each reader of the atlas according to his own imagination and critical introspection. The “topics” section tries to focus and analyze what we are personally sorting out from the archive, our own multiple paths through the references, but, as we talked about in the previous answers, other topics might be identified through other uses of the site as an atlas, since personal sensibilities and imaginations could travel through it following different routes.

(A series of links to better illustrate the examples in this answer: )

- The Bloodbath of B-R5RB or Battle of B-R5RB

- Spaceships worth more than $200,000 destroyed in biggest virtual space battle ever

- Star Trek Online’s Memorial For Leonard Nimoy

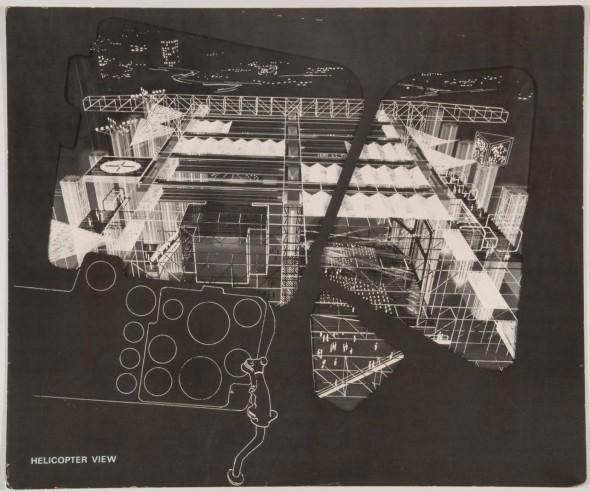

Imaginary buildings: Cedric Price’s ‘Fun Palace’.

Imaginary buildings: Cedric Price’s ‘Fun Palace’.

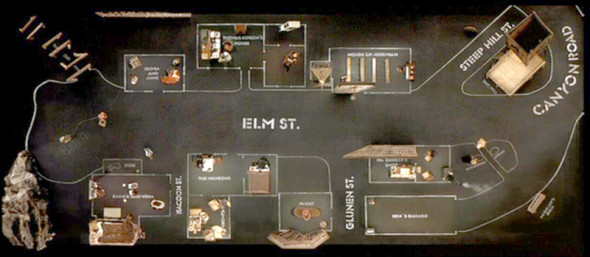

P.V.A.: Linear drawing techniques are very present in SOCKS, particularly specific systems of representation which are specifically architectural, like axonometric projections, plans and sections. This is relevant to me, as I personally find that the prominence of “collaged scenes”, renders, photography and video in architecture’s main channels of communication is an indicator of the extent to which advertising immersive techniques have leaked into the culture of architectural representation and narrative. Of course, this is part of contemporary conditions, and as such it’s something architecture has to explore and try to take advantage of… But I think we have to gain awareness about the limitations they impose as narrative devices; we have to ask ourselves about the conditions we generate or promote when we privilege this type of depictions over other possibilities. While advertising techniques are often based in one-point perspective projections (whether static or in movement) that reproduce our experience of space in order to propel the projection of the individual self into a scene or vignette, architectural analytical drawings—plan, sections, isometric and oblique projection— maintain a partial disengagement of the observer. They give us the opportunity to step back and take the critical point of view of a disengaged observer, so scarce in our immersive visual culture. Other disciplines that deal with narrative, like art, literature or film, sometimes explore the self-awareness of the observer which is implicit in architectural drawing — I’m thinking of the the aerial point of view, typical of urban plans, in the project “Officer Involved” by Josh Begley or the use of the “plan” in Lars von Trier’s Dogville.

Screenshots of the film Dogville. Lars von Trier, 2003.

Screenshots of the film Dogville. Lars von Trier, 2003.

Screenshot of the website of the project “Office Involved” by Josh Begley, 2015.

Screenshot of the website of the project “Office Involved” by Josh Begley, 2015.

Both projects also offers a “section” of the contemporary mode of vision, which fluctuates across both sides of every scene (reality and representation, experience and narrative), involving subjective and collective dimensions. These visual approaches, able to disrupt or amplify the perception of our environments and how we relate to them, somehow remind us that individuals and society have to gain self-awareness and disengagement from our habitats in order to re-conceptualize and highlight the unnoticed forms of enclosure, boundaries and barriers that define them. Analytical linear drawings like those you offer in SOCKS could help to this aim. Does your interest in linear and analytical drawing relate to a will to uncover misconceptions about our environments? Do you think that there are particular narrative devices or representation techniques that might be more capable to counter the regular perception and dominant assumptions about them?

The choice of referring mostly to linear drawings in our selection was made since we first started to write about architectural projects on the site. It was a natural decision for us, since one of the reasons for editing Socks is to find a way to place some order in the multiplicity of images which we encounter daily on the internet and in magazines.

Posting linear drawings helps us to retrieve the deep meaning of the project beyond its advertised image, (which you refer to as well), and properly explore the architectural specificities we discussed about in the last answer. There are also other reasons: linear drawings, especially plans, let different and faraway works to be easily comparable; since they do not integrate noisy addictions for the bare purpose of communication, they are among the best tools to reveal those architectural permanencies we keep on talking about. A plan is often stripped of any notion of style and is focused on the production and arrangement of spaces, it emphasizes the presence and specific role of the architectural elements, especially walls, a subject we are increasingly interested in, and the way the structure dialogues with the definition of spaces, underlining the hierarchical or the isotropic nature of a project. It is not by chance that one of the first topics we introduced is the one of “Dysfunctional Plans”, mostly domestic plans embodying a sort of resistance against standardization. Through this topic we aim to employ architecture and one of its fundamental means of representation as an instrument to critically read society, in that a plan of a built or unbuilt project becomes an almost permanent trace of a transitory societal and familiar condition or an intrinsic response to that.

Bill Viola, ‘Catherine’s Room’, 2001 (click to enlarge). Image via: Mediapart.

Bill Viola, ‘Catherine’s Room’, 2001 (click to enlarge). Image via: Mediapart.

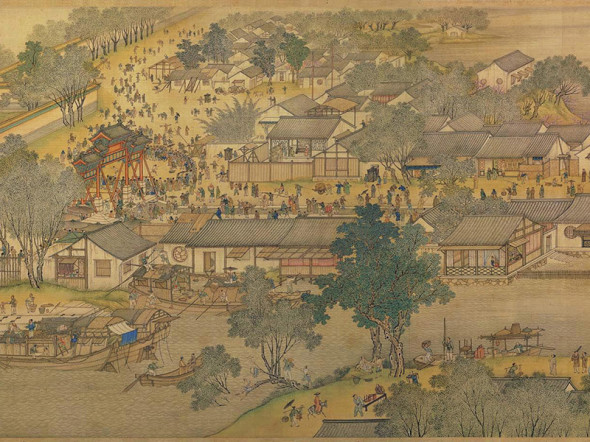

We are also interested in plans, sections and axonometric projections as narrative devices able to coherently host diachronic narratives within the same physical frame: you refer to the example of Dogville, but we also think of the work of artist Bill Viola, particularly his “Catherine’s Room” which places on the same level events happening in different time frames and connects them together through a continuous animated perspective section. The natural models for Bill Viola were Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel and Paolo Uccello’s “Predella dell’Ostia Profanata”. In a sense, all these works exemplify how peculiar architectural devices might be borrowed by other disciplines for iconographic purposes.

Axonometric projections are for us a subject apart from the rest: we tend to use them a lot in our own practice, especially in projects which have an impact on the urban level, because they enable us to let different scales cohabit in a single drawing and provide the opportunity to show the relationship between the single domestic unit and the whole context. Axonometrics allow to mix the technical and the descriptive and to somehow display one or multiple narrative levels within the main frame. On Socks, we are thus building a repository of examples of axonometric projections, mostly provided by artists and illustrators, in order to explore their versatility.

We do not think that there are specific techniques which might be more capable to counter regular assumptions, but we believe that it is more within the critical understanding of the reader to go beyond the advertising patterns and to unveil the tools used in a work to convey meaning.

Paolo Uccello: Scene 2 from ‘Predella dell’Ostia Profanata’ (Miracle of the desecrated host), 1467-1469. Image via WGA.

Paolo Uccello: Scene 2 from ‘Predella dell’Ostia Profanata’ (Miracle of the desecrated host), 1467-1469. Image via WGA.

Giotto: Panels from the Scrovegni Chapel, 1305.

Giotto: Panels from the Scrovegni Chapel, 1305.

Axonometric Projection as a narrative device: ‘Along the River During the Qingming Festival’ by Zhang Zeduan (12th Century) in an 18th Century remake.

Axonometric Projection as a narrative device: ‘Along the River During the Qingming Festival’ by Zhang Zeduan (12th Century) in an 18th Century remake.

P.V.A.: These examples are very eloquent, because they play with both “immersiveness” and disengagement, mixing the one-point perspective projection and the analytical view typical of the section. And they belong to very distant cultures and epochs. Spatial narrative is such a fascinating realm!

Davide Tommaso Ferrando.: As you noted in the first part of the interview, the specific characteristics of web communication, and particularly the easiness with which materials coming from distant epochs can be gathered in one same place, are shifting our perception of the past, both as a matter of interest and as a design tool, making it immediately available for further speculation. As much as this phenomenon is typical of our times, I find it hard to read it as something “new”, as it can be interpreted as an exacerbated version – “harder, faster, stronger” – of the postmodern condition, whose outcomes are very well known to architects. If I think of Andrew Kovacs’ collages made of floor plans of historic buildings, for example. I understand that this way of recomposing references is typical of our time, but again I still feel pretty inside postmodernist “citationism”. In what way do you argue that today’s approach to the past is different from the one developed in the second half of the past century?

We believe that the availability of information from any epochs which network culture has provided and which places all periods mostly on the same level, on the one hand prevents us to understand the world in historical terms, but on the other, it might help to avoid the obsessive need for a style to be “original” and to become somehow representative of the moment. While many authors argue that it currently exists an inability to produce anything “new”, we try and look for a positive outcome of the “network culture” condition, namely: the possibility to evade the continuous production of easily labelable new products which as fast and easily become obsolescent and get discarded. What we are trying to embrace, here, is a very optimistic position. We are referring to a possible means to escape the easy commodification of images and works, in order to come back to the production of specific architectural knowledge. For this possibility to be reached, subtle references from the architectural production of the past must be selected and analyzed for their ability to condense meaning and not for their visual appeal.

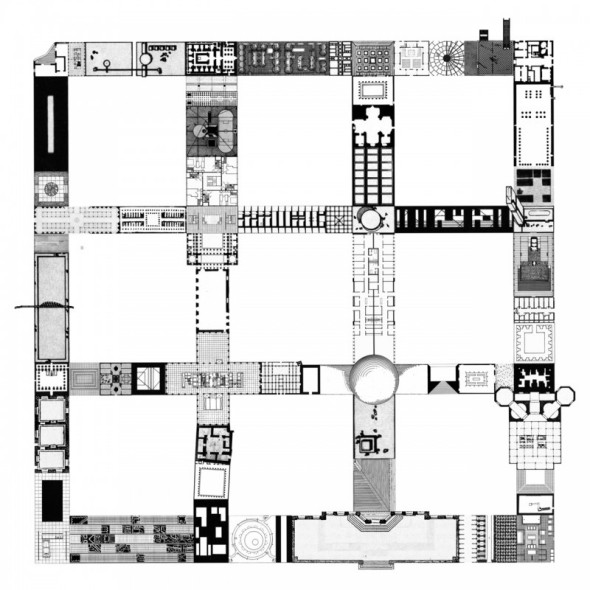

Andrew Kovacs (Archive of Affinities) ‘Plan For A 9 Square Grid’.

Andrew Kovacs (Archive of Affinities) ‘Plan For A 9 Square Grid’.

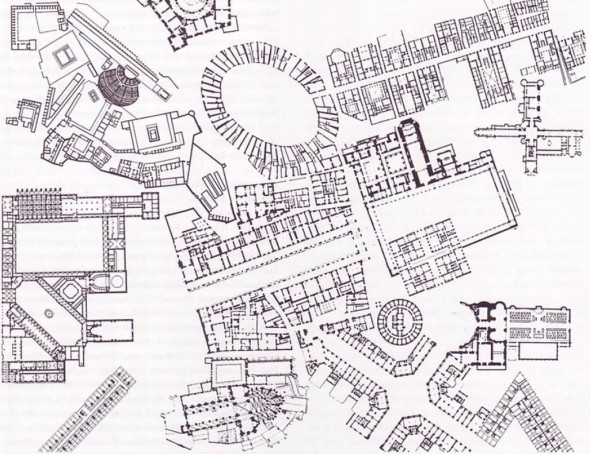

‘City of composite presence’ : historical typologies assembled to form a conceivable urban texture. Hans Kollhoff, David Griffin, published in 1978 in Collage City by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter.

‘City of composite presence’ : historical typologies assembled to form a conceivable urban texture. Hans Kollhoff, David Griffin, published in 1978 in Collage City by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter.

In a way, this is the opposite of a revival of postmodernism, mainly because we don’t think contemporary use of the past is for narrative-sake or in order to produce allegories. We are not living a conscious reaction to a previous condition or a dogmatic belief, but a natural outcome of an available situation which is challenging the way we learn and how we experience culture on many levels. As argued by Kazys Varnelis, Andrew Kovacs’ plans may superficially recall Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter’s postmodern collage techniques as explored in their Collage City, but they don’t retain any trace of violent encounter between historical fragments and thus they lack a central aspect of the post-modern condition: the inability of ever producing a “whole”.

Despite the inevitable generalization, it seems that the characteristics of the web may open interesting perspectives and somehow challenge the worries about the supposed stagnation of culture, the impossibility of producing anything significant in contemporary times, and similar rants.

D. T. F.: The kind of publishing-work you are doing with SOCKS is of great interest to me, because it positions itself in an “in-between” territory between traditional blogging and the new trend of curated archives. Of blogging, you maintain the denotative interpretation of the published matter, which you enrich with short texts that provide readers with a direct understanding of the posts’ content; of curated archives, you maintain the connotative character of the editorial project, which is designed as an atlas through which readers can easily move and produce their own meanings via spontaneous association of images. By doing this, I believe, you are managing to publish digital content in a fast but not superficial way – which is something of great value in the present moment. Why did you choose this particular structure for Socks? Are there editorial projects that you have taken as reference, or reacted to, when designing it? Is “speed”, as the condition through which digital content is mainly experienced today, a matter of interest (or concern) for you?

We have never consciously chosen a specific framework for SOCKS, but it sort of evolved naturally as the content changed (and still is). We tried to adapt it progressively to a format which fitted our intent for it to be at the same time a repository, an atlas of differently connected subjects, and a place for open exploration of multiple contents. Actually, we are still looking for a structure that better allows for more levels of reading to coexist: the (almost) daily update, the map which is recomposed by each reader and the critical section of the topics which we would love to implement in different ways.

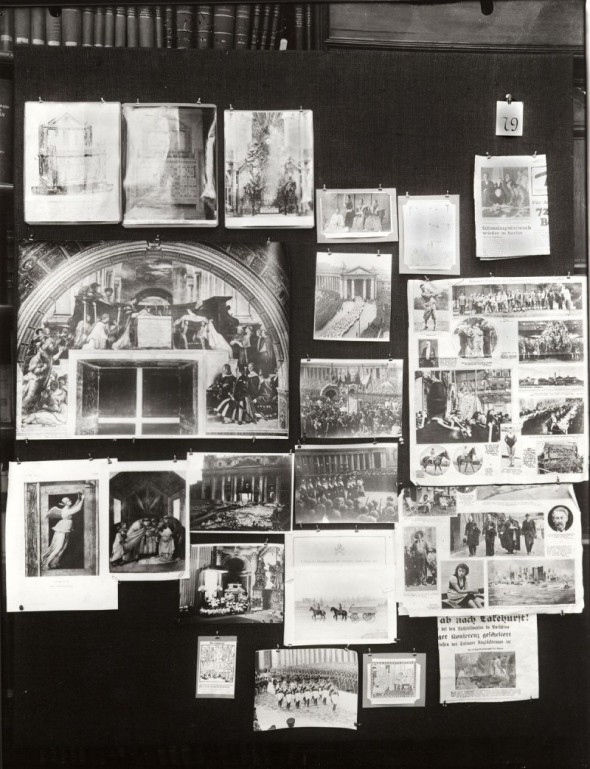

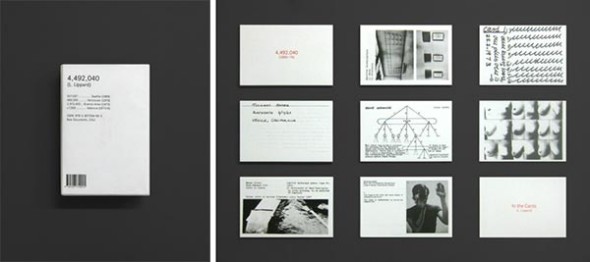

SOCKS began as a conventional weblog, featuring texts on different subjects and a colloquial writing style, without ever being a personal journal. While we have abandoned this model we have probably kept some aspects of it, which is why you see it today as a hybrid between different forms of online communication. We have probably been inspired, and still are, by a number of different online editorial projects but it took us some time to recognize what we were specifically doing and in which direction we wanted to bring it. Just recently we are figuring this out a bit more clearly, especially by studying paradigmatic “Atlases”, i.e. Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne after the rediscovery and the interpretation of Georges Didi-Huberman, and we are trying to react to it. Another important reference for us is the “Numbers shows” by curator of conceptual art Lucy Lippard who, already between 1969 and 1974, pointed to the direction of dematerialisation and detachment from the value of original artworks. Her exhibitions recomposed what would only be fragments, creating a general narrative which allowed for the single works to resonate one with the other.

Aby Warburg’s ‘Mnemosyne Atlas’ – Plate 79 (‘Mass. Eating god. Bolsena, Botticelli. Paganism in the Church. Miracle of the bleeding host. Transubstantiation. Italian criminal before extreme unction.’). Image via NDLR.

Aby Warburg’s ‘Mnemosyne Atlas’ – Plate 79 (‘Mass. Eating god. Bolsena, Botticelli. Paganism in the Church. Miracle of the bleeding host. Transubstantiation. Italian criminal before extreme unction.’). Image via NDLR.

‘4.492.040’ (one of the Number Shows, curated by Lucy Lippard, between 1969 and 1974). Image via worldfoodbooks.

‘4.492.040’ (one of the Number Shows, curated by Lucy Lippard, between 1969 and 1974). Image via worldfoodbooks.

In our opinion, the critique of “speed” in the age of the internet and social networks has become a cliché: nowadays, in the web there is a lot of room for deeply thought content, complex debates and profound researches that may even last for years. Speed as a condition is just a part of the picture, perhaps the one which is easiest to point out. In our work on Socks, speed does not concern us that much, and it may only be related to the frequency of single posting. We made a sort of recurring exercise out of it: to be able to synthesize in short or medium-size texts the reasons why we believe a certain subject has a specific interest, but often, in fact, articles which are published today have been started months ago. Furthermore, we don’t believe the isolated posts to have greater relevance respect of the extended writing crossing all the single pieces as a whole. What is central is the creation of a non-linear text throughout the website.

On the other hand, since we don’t talk about news, we don’t feel the urge to quickly react to daily events or to be up-to-date with anything happening today, neither have we felt obliged to form and give our quick opinion on any debate which is developed daily.

P.V.A.: Another key contribution of SOCKS to present debates, in my opinion, is how it seems to be indirectly reclaiming the role of architectural design —particularly geometry, structure, composition and form— in the re-opening of the field of possibilities for our environments to be re-configured, in a moment when architectural specificity is considered almost irrelevant to that end. In embracing the encounter with other fields along the past 20 years, architects have often overlooked architectural specificities, as if they were avoiding the challenge of re-elaborating them —maybe conditioned by a feeling of guilt or shame regarding other architects’ flirts with economical power. However SOCKS, even if it’s far away from the wanting of protecting architecture discipline from the encroachment of other fields, has no fear in embracing the fields that emerge when the specificities of architecture are approached by other disciplines. The affinities, relations and correspondences through distant fields presented in Socks —music, film, theatre, art, literature, etc.— seem to be largely (although not only) based on architectural specificities. Is specificity what you refer to when you express your desire to “acknowledge and employ the permanencies, the quality and the shared knowledge conveyed through the history of architecture”? Do you think other fields can help us find in architecture’s specificities registers we wouldn’t know they had? And what about the reverse pattern?

Two orientations coexist in SOCKS: the connections among an open sphere of multiple subjects and the research for the specificity of the architectural project. Through Socks we reclaim the role of architectural specificity as a subject in the shaping of our environments, an acknowledgement of the power of its own attributes without the need to adopt a multidisciplinary approach in order to provide the tools for the production of a project.

We do refer to form, geometry, structure or composition mostly as conveyor for content, materialization of socio-economic conditions as well as bearer of a hidden order. We believe there is a recent tendency to stress architects and architecture’s responsibilities for the failure of societal models and as a means of oppression and exploitation, while usually forgetting what architecture is in large part, a materialization and reproduction of economical and social structures in a specific mode of production. This is not meant to alleviate the discipline of any responsibility but we believe that the good or bad impact of architecture on the social environment must be observed within its own rules and possibilities, which fall mostly inside its own specificities.

At the same time, we employ the filter of architecture as an agent of knowledge, a tool to understand and apprehend the world, therefore the specificities of the discipline become the lens through which we select and comment works and researches from within other fields.

Imaginary buildings: OMA’s Très Grande Bibliothèque, 1989.

Imaginary buildings: OMA’s Très Grande Bibliothèque, 1989.

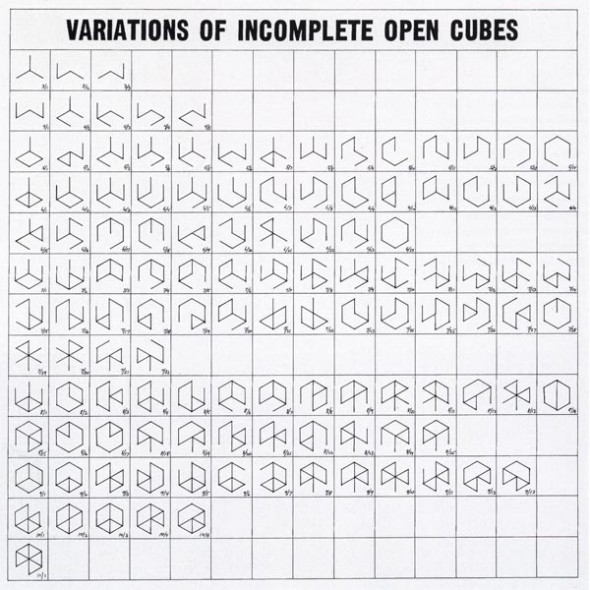

Sol LeWitt: Variations of incomplete open cubes, 1974.

Sol LeWitt: Variations of incomplete open cubes, 1974.

In a way, when single features inherent to the architectural discourse are directly or indirectly explored by foreign practices, they get dissected, analyzed and made explicit as in some sort of laboratory investigation. Rarely could they have been so autonomously isolated within the complex realm of architecture. For example, some of the drawn works by Sol LeWitt we repeatedly post, explore form in its bare nature, questioning its limits in perception and communication. (Not by chance LeWitt used to work for an architect). In other cases, artistic researches bring previous architectural visions to the extreme consequences by extrapolating potential narratives, acting as “testing grounds”, or providing an immediate visualization of an attitude taken to its extreme.

Another way of cross-referring heterogeneous fields is by establishing a dialogue between -mostly compositional- methods. This is the case of a series of posts about “absurd musical partitions”: scores created by contemporary composers who aim to undermine conventional musical structures and introduce abstraction and chance in written codification, and that we try to confront to different ways of encoding architectural works.

D.T.F.: Insisting a little bit more on the new availability of references allowed by the advent and consolidation of web media, there seems to be something new in the way in which ideas spread today, which in my opinion is related with the fact that digital images are becoming their principal means of transportation. Content, in other words, is much easier to reach, but the way in which it is distributed (mainly through images) and the speed at which it is received (a very fast one) often reduce meanings to their visible dimension, in an accelerating process of “flattening to the surface” of architectural discourse. Although this may sound as something problematic -and in many cases it is- I have the feeling that this condition is also capable of opening up to new ways of disposing of architectural knowledge, and therefore of designing. As you are constructing, through Socks, a kind of architectural knowledge that is strongly based on images, do you think that this can affect (and how, if you do) architectural communication and design?

The increasing transmission of content through the means of images is obviously a trend that has been intensified with the advent of network culture, but that was actually a subject of discussion already after the invention of photography. The role of iconography as a communication device has indeed been very relevant throughout the whole human history. The subject of the role of images and their ability to convey content or to condense ideas is very vast and goes far back in time; it would be hard not to reduce it to some banal statements in the short space we have here. Nonetheless, since we have already cited him, we would like to quote ”Atlas ou le gai savoir inquiet” by G. Didi Huberman when the author, referring to the concept of “Lesbarkeit” (legibility) in Benjamin, points out that “reading the world is also to connect the things of the world through their secret and intimate relationships, their correspondences and their analogies”. In this sense, creating an atlas (or a Tumblr, a Pinterest board, or other contemporary versions of the atlas), working on the associations among images gives to content a new reading and produces “knowledge through imagination”. We suppose this is what you are referring to when you talk about “new ways of disposing of architectural knowledge”.

In the case of architecture, the specific kind of images which drawings are, have always condensed the central discourse on architecture itself. A distinction has to be made for that imagery related to architectural “advertising”: the infamous “renderings”, and their generic atmospheres and population. Not only are most of these images very mundane, but we feel that the practice of architecture in itself may have intrinsic issues with them. In fact, architects are more and more asked to produce a complete and convincing image of the project at a very early stage of the design process (most of the time for a private client of for submitting a competition entry). Any architectural project needs to naturally evolve, to go through different phases of design, but it gets already stuck in that very first photo-realistic image. So, in a sense, the renderings act against architecture, they sort of boycott architecture. It is not by chance that many young architecture practices began using other techniques to illustrate their work (collages, non photo-realistic perspectives, etc.), although this is also unfortunately turning into a fashionable trend.

Going back to our work in SOCKS, for us it is essential the fact that we don’t refer only to architectural projects, but try and broaden the discourse on other artistic researches in order to mark the correspondences and to structure a larger analysis. When we feature architectural projects we try to give emphasis to bi-dimensional projections like plans, sections and elevations; when they are relevant, we believe that the description of the way these drawings are conceived, the way they underline the geometrical structures, how they are able to orient the life of the inhabitants and the sociopolitical conditions they reflect, may communicate the nature of a project at the same level of a written essay. This approach helps a lot in making the selection of projects we might want to publish; if the technical and spatial drawings have nothing interesting to communicate, we generally won’t feel the need to publish the project. If this process can affect architectural communication and design, we are not able to tell. We believe Socks is still a very “underground” website, even though in the era of internet nothing is really underground anymore. Our readership is pretty limited compared to major architectural magazines or websites, so the influence of our discourse is of course marginal.

About the speed of consumption related to images, we increasingly believe that this criticism could be applied to any other means of content transmission, texts and books included. Our teacher of history of contemporary architecture, Prof.Giorgio Ciucci, used to say that right after making a book’ photocopies, many students believe to have already “magically” studied it. This is exactly the same with digital images, of course the meaning transmitted will be superficial if you limit yourself to a fast screening or a “share”, but they can be complementary to text and equally rich in meaning and content if you spend time in analyzing and dissecting them.

D.T.F.: The spread of curated archives is bringing to the fore, in an extremely evident way, the importance of personal taste as a cultural producer, being it the implicit mechanism that steers the researches editorial projects like Socks are based on. In our age of broadly and immediately available information, in other terms, the construction of taste -which we could intend as the capacity of choosing what to publish and what not- has become an essential tool for the production of coherent narratives capable of reacting to the undistinguished and confused tsunami of data we are confronted with every day. How would you define the kind of “taste” that acts behind Socks (what are, in a broader sense, the things that catch your attention and where do you think that this interest come from)? What experiences (academic, professional, personal) have been mostly responsible, according to you, for the formation of your taste?

We are forming what you call a personal “taste” by working on SOCKS and not the other way around, but we are not very comfortable with this term because it implies a sort of (almost moral) judgement, the idea of good or bad taste, which does not really interest us. We follow a very intuitive process in the selection of subjects and we are recalling the emergence of some interests by looking back through the archive. In a way, it is a sort of retrospective psychological analysis which allows for some recurring patterns to progressively emerge. Sometimes the selection is made out of pure curiosity and it starts from the fact that we don’t really understand a project or a work and writing an article becomes our way to apprehend it. Sometimes our attention is caught by a specific image or a slice of text in which we believe to foresee some fragments of a larger discourse.

We somehow started to be interested in contemporary art by studying some movements of the 1960s and 1970s, mostly conceptual, minimalism, body-art and land-art and we believe that this research still plays a major role in the way we look at any work. Another experience which has a lot to do with the way we confront with projects were the History of architecture classes we took during the second and third year at the University of Architecture of Rome with Professor Nicola Pagliara (now teacher at the EPFL) and Giorgio Ciucci. For both courses there were a couple or three intermediate written tests which required the students to draw by heart a large number of projects, in plan, section and elevation. For one test based on the Renaissance period there were about a hundred of drawings to be remembered. The only way to be able to do that was to understand well the logics behind the projects, especially the geometrical ones, and to be able to reconstruct the projections out of them. This is really what you referred to before: communicating knowledge through images or drawings, but in order to absorb this knowledge you had to work on that, you had to know the project on a deep level and understand its intrinsic rules.

P. V. A.: In the new section of SOCKS, “topics”, you have decided to elaborate very specific sub-themes that maybe could lead to an article or other material in the future. As you know, Davide and I are investigating connections between editors propelled by social networks. While editors and writers often interact in social media, collaborations are not so frequent. In this sense, have you thought of inviting colleagues-editors you have affinity with to curate a topic for SOCKS?

We wished to start this “topics” section since a long time as we felt the need to organize some recurring themes in a more explicit way, even if they reveal themselves as unconventional subjects, and to broaden the critical character of our work. The topics also display a connection between our work on Socks and the specific interests which shape our design practice at Microcities: they are able to establish a dialogue with some themes that we are developing through our projects, especially the theoretical ones, and that we wish to further explore and incorporate over time. As you noticed, the idea is to expand the topics in depth, to write longer introductory essays, to add new posts and to multiply their number over time. Of course, it would be interesting if this could open a space for collaboration, by including other people to curate new topics or to contribute to an existing one. We previously tried to ask friends to collaborate by writing guest posts, but it didn’t really work out, maybe because we are used to a certain routine of publishing and it is not easy for someone else to jump in. The topics section has a different timing so your suggestion is more than welcome: if you are interested in it, it would be a pleasure for us to invite you and Davide to be the first.

P.V.A.: Thanks for the invitation, we will be very happy to contribute!

Going on with SOCKS’ topics, throughout this new section you express an interest in countering canonical approaches, making space for dysfunction, dystopia, contradiction, paradox or failure. In this sense, perhaps SOCKS is countering the so-called pragmatic approach in architecture, which has attempted to redefine ethical concerns in design as something ‘in the making’ and ‘proper to situations at stake’, often to obliterate the philosophical aspirations that architecture had in the 80’s. I think many of the contents in Socks succinctly reauthorize architectural design as a way of interrogating reality, somehow going beyond the situated and contingent character of architectural practice, which is key to pragmatism. In fact, you seem to be interested in recovering architecture’s role as a source of knowledge, or in other words, a way to interrogate current conditions beyond the response to a particular situation, problem and context. What is your position in relation with pragmatic attitudes? Are you consciously separating from them? Is direct action and immediate intervention the best way for architectural design to engage in social, political and ethical issues?

We do not believe architecture to be a straightforward vehicle to solve problems. In fact, we are critical of practices which propagandize their social or ecological engagement and advertise their work as an optimistic agent of change. It is not in our interest to promote this kind of agenda. Rather, as you point out, Socks aims at extrapolating the ability of architectural design to become a tool for questioning ‘reality’, or better say, to unveil the structural categories hidden behind the surface. Therefore, there is space for controversy, failure, dysfunction and contradiction: generally, we don’t consider these terms to be negative per sé.

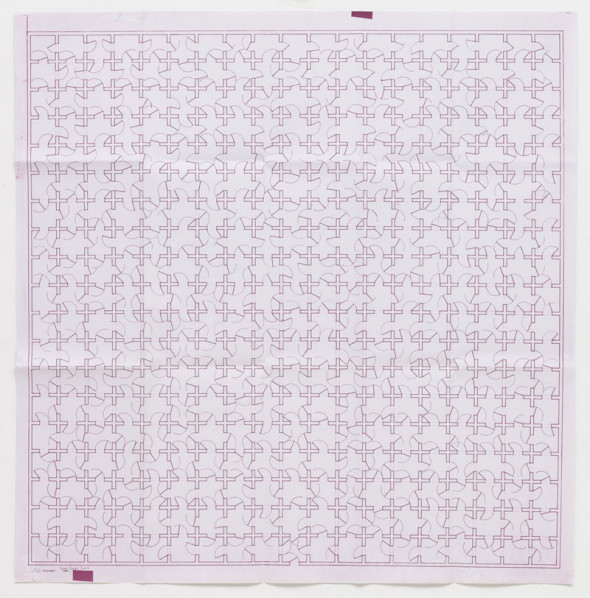

Dysfunctional plans: Leon Ferrari’s “Heliographias“, since 1980.

Dysfunctional plans: Leon Ferrari’s “Heliographias“, since 1980.

We also agree with a position Pier Vittorio Aureli made clear in an interview published by our friends of Plan Comun / Onarchitecture: that what is advertised as architectural pragmatism (as in a project statement or in the superficial innocence of a competition program) usually hides an ideological framework. Dystopian, dysfunctional and theoretical projects can be used as legitimate tools to unveil the ideological discourse, the consequences and the risks of a model of thinking, producing and celebrating architecture.

We think that the 1990s embracing of late capitalism through pragmatism and celebration of pure design “smartness” has now definitely revealed its drawbacks. Although we are still observing phenomena of hyper-mediatization of architectural gestures, a new ground for a critical debate is surfacing.

P.V.A.: Sure it is —and SOCKS is a great prove of it! Thank you very much for this intense conversation, for your references and relations, and for the interest and engagement you have put in your answers. I love the fact that you equally use words and images to respond. As you suggested in our emails, let’s keep this conversation open… It has been a real pleasure!

Seville/Madrid/Paris — 2015